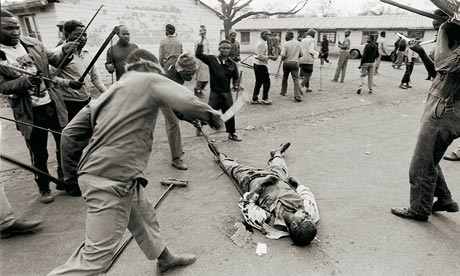

Mob attack, by Greg Marinovich

'I was gutted that I'd been such a coward'

It was my first time in a conflict situation, and I was quite unprepared. I was on my own inside a migrant worker's hostel in South Africa. Suddenly all the men started picking up spears and sticks and clubs, and racing off. So I followed them. They were trying to get into one of the dormitory rooms, and there was someone inside pressing against the door. Eventually, the door was flung open and this guy with a scarf tied like a turban around his head came dashing out. He looked me straight in the eyes, and then took off.

All these other men started chasing him, and he hadn't gone far when he was brought down. About 15 or 20 men were all around him, hitting and stabbing and clubbing. And I was right there, photographing it. On the one hand, I was horrified, and at the same time I was thinking: what should the exposure be?

It was the old days: analogue, manual focus, crappy cameras. I felt torn between the horror of what I was seeing and trying to capture it. I was also thinking, how am I going to survive this? Because sooner or later these people are going to say, "There's this guy taking pictures of us committing murder." I was 1km from my car and the nearest outsider.

They killed him. And then one of them turned and said, "The white guy's photographing." Everyone leapt away, and I said, "No, it's fine, it's fine. Why did you kill him? Who is he?"

I was thinking, "I'll spit on his body, I'll kick this corpse, I don't care – I'm going to survive this." Thankfully, I didn't have to do that. They pulled his ID out of his pocket: he was from another tribe. Then two of the killers posed and said, "Take a picture of us." So I took a picture and walked away. All the time I was expecting somebody to say, "Wait, that guy musn't leave." But I walked off, got into my car and got the hell out of there.

It was my first exposure to such a thing. And although, as a journalist, my reaction was fine, as a human being I felt I'd really let myself down. It wasn't how I'd expected I'd react – I thought I'd try to intervene, or do something more noble. Yet I hadn't. I was really quite torn up about that. I was gutted that I'd been such a coward. From that moment, I was determined that, no matter what, I'd try to intervene and save someone if I could.

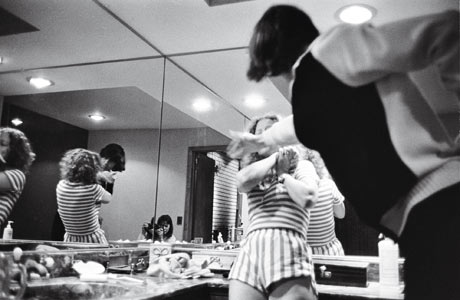

Domestic violence, by By Donna Ferrato

'I saw that he was getting ready to hit her and I took the picture'

Photograph: Donna Ferrato

Photograph: Donna FerratoI try to get into real people's lives and tell their stories. I'd been photographing this couple for a while. I was in their home, sleeping down the hall with my baby daughter, when I heard the woman screaming. It was about 2am and I could hear things crashing and breaking in the master bedroom. I put my little girl in her basket and put her in the closet, because I knew the husband had a gun. And then I grabbed my gun – which is a little Leica M4 – and went running down the hall. As soon as I walked into the bathroom off the bedroom, I saw that he was getting ready to hit her and I took the picture. I thought, if I don't take this picture, no one will believe this ever happened. That's the first picture I took that night. His hand was in the air and I was shocked out of my wits. I had never seen him do that. I saw him being a little rough with her, shaking her up earlier in the day, but he wasn't beating her. That was the first time I saw him commit an act of violence, and my instinct was to get the picture first.

But after I got that one picture – because I knew I had it – I didn't just keep shooting. I wasn't like those war photographers who just stand there: bang, bang, bang. When I saw his hand go back to hit her a second time, I grabbed his arm and said, "What the hell are you doing? You're going to hurt her!" He threw me off and said, "She's my wife and I know my own strength, but I have to teach her a lesson that she can't lie to me", but from that point on he didn't hit her again.

When I was taking other photographs for I Am Unbeatable, my book on domestic violence, I was there first as a photographer, not as a social worker. Yes, I would always be divided about whether to take a picture or defend the victim, but if I chose to put down my camera and stop one man from hitting one woman, I'd be helping just one woman. However, if I got the picture, I could help countless more.

For more information on Donna Ferrato's project on domestic violence, visit iamunbeatable.com.

Pro-hunting protests, by Graeme Robertson

'He said, "Help me, please help me", and I didn't do anything'

Photograph: Graeme Robertson/Getty Images

Photograph: Graeme Robertson/Getty ImagesThis picture was a taken on quite a violent day. The police were really up for it. The demonstrators were really up for it. Everybody was getting hit hard. I was flung to the floor by a policeman. I was lying there, dusting myself, ready to give the policeman a bit of my Scottish abuse, when I saw a man being wrestled to the ground for not doing what he was told. He hadn't done anything wrong, but as he was lying on the ground, the policemen were abusing him and being really aggressive with him, hands round his neck, that kind of thing. I picked up my camera and he said, "Help me, help me. Please help me." And I didn't do anything. I took a picture – and he got dragged off.

When I got home that night, I felt a bit uneasy. I thought, "I didn't really do anything there. I didn't really help." But is it the job of a photographer to get involved in this sort of thing? For five years, I covered an awful lot of conflict – Baghdad, Afghanistan, all across Africa, the Middle East. The stuff that I saw there… On my first assignments in Iraq, I really struggled with it. It caused me so much stress, I got alopecia and lost all my hair all over my body. Just from thinking about all these things. The first time I experienced it, it actually stopped me taking images I really wanted to take or should have taken, because I was so mixed up and thinking, "Should I be doing this or not? I found it very difficult. But through experience, it's sad to say, you get immune to it. And then you can concentrate on your photography, and you feel that is your power.

If you manage to get a picture that shows the scenario, that is you helping them. I'm not in this situation to help them physically, but that is what I'm on this planet to do.

I know of photographers who have thought, "I can't not help this kid" and taken the kid away. And they've got themselves into so much trouble. Because they don't know the situation or how things work. They have a different culture, different views, different medication, and often in a situation like that you end up being more of a hindrance than a help.

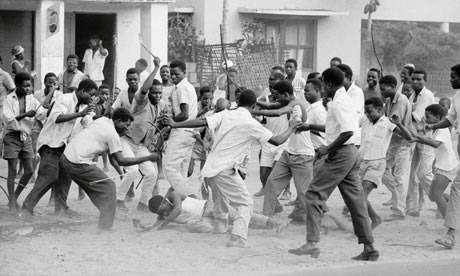

Stoning, by Ian Berry

'It never occurred to me to do anything'

Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

Ian Berry/Magnum PhotosI was travelling around Congo with Tom Hopkinson, the editor of Picture Post, and a couple of other photographers. I was in the front of the car and I spotted a crowd coming down the street, chasing one man.

We discovered later that the only sin this man had committed was being in the wrong tribe and in the wrong area. The crowd chased him and threw rocks at him; children and adults beat him with sticks. Finally, he was totally exhausted and fell to the ground quite near where I was standing. And I went on photographing.

To my shame, it never occurred to me to do anything. To start with, we were white. On our own. The other two photographers didn't get out of the car. Suddenly I realised that Tom had walked into the crowd and stood over the guy. People were so amazed, they just stood back. The man was able to stagger up, around a corner and escape. It was an amazing thing to do. Tom undoubtedly saved the man's life. And, frankly, it had not for a moment occurred to me to intervene.

When you're working with a camera, you tend to disassociate yourself from what's going on. You're just an observer. We were there to record the facts. But there are moments when the facts are less important than somebody's life.

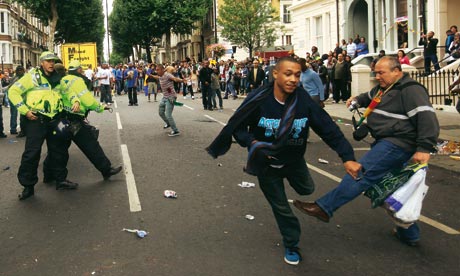

Stabbing, by Oli Scarff

'I don't know if I would have had the bottle to put myself in mortal danger'

Photograph: Oli Scarff/Getty Images

Photograph: Oli Scarff/Getty ImagesI'd been assigned to cover the Notting Hill carnival, so I'd been down there early, capturing the colours and the floats and the jerk chicken. The carnival was winding down, there were a lot more police on the streets, and I noticed a group of about three or four start running. There was nothing else to do, so I ran after them to see what was going on.

It was a chaotic scene, and my first instinct was to take a couple of photos immediately, to record what was happening. It's something I've conditioned myself to do: to get a shot in the bag before you can fully assess the situation. After that, my attention was drawn to a man who had been stabbed, and who was bleeding profusely. I photographed the police and paramedics treating his wounds and trying to keep him conscious, which thankfully they did. It was only after that when I noticed that the two pictures I shot at the beginning included this scene of the man with the knife and a guy attempting to trip him up. I'd manage to capture that in a split second. From the trajectory of the two images I have, it looked like he was just about to run past my left shoulder. He would have passed me in an instant.

To be honest, even if I had been aware of what was going on, I don't know if I would have had the bottle to put myself in mortal danger. It's hard to know, though: those decisions come down to a spur-of-the-moment instinct. But, fundamentally, my role on that day was to document what was happening. In the corner of the picture is someone else taking a photograph. I think, perhaps, there is an innate human desire to record these kind of things. And the facility to do so has now been put in everyone's pockets.

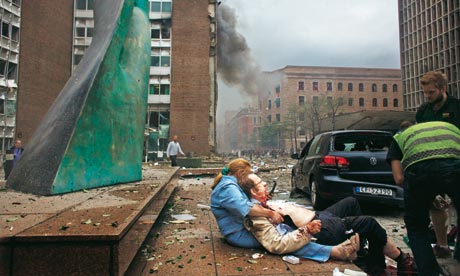

Bomb aftermath, by Hampus Lundgren

'I became a photographer and not a person'

Photograph: Hampus Lundgren

Photograph: Hampus LundgrenI'm a freelance photographer and I had my first summer job working at a newspaper a block away from the government offices in Oslo. Up until then I'd been doing feel-good stories, following a group of male synchronised swimmers, that kind of thing. When the bomb went off, I saw a fireball in the air, then a shockwave came towards our office, knocked people to the ground and shattered all the windows. We had to evacuate, so I grabbed the camera on my desk and started running towards where the bomb had gone off. I knew there was the possibility of a second explosion and I was afraid the buildings would collapse, so I gave myself 10-15 minutes to take pictures and then get out.

This was one of the first things I saw. My mind shut down a bit, I think, because I don't remember taking this picture. I just felt adrenaline. I became a photographer and not a person. It didn't cross my mind to talk to them. The man was being held up by his wife. He was badly injured, and getting help from other people nearby, including an off-duty policeman. The others I could see were already dead. I don't know first aid, so I thought the thing I can do, and what I do best, is to document this, show people what happened.

I met the couple a few months later to see how they were doing. He was severely injured by shrapnel, and had had his right leg amputated. They told me they were really angry at the time, because the first thing they noticed when he was lying on the ground was a photographer taking a picture of him. That made me feel guilty, but later, when I showed them the image and spoke to them, they said they were pleased these pictures were taken because it helped them to remember. That helped me a lot, to feel I hadn't used them.

London riots, by Kerim Okten

'I wanted to shout "Stop!"... but I was frightened'

Photograph: Kerim Okten/EPA

Photograph: Kerim Okten/EPAIt was 8 August, day three of the London riots. I was in Hackney, and I watched this group approach a line of shops behind shutters. They obviously knew which shop was the newsagent because they went straight for it, breaking the locks on the shutters, then smashing the door, breaking in and looting anything valuable: money, alcohol, food, cigarettes. Dozens of people began queuing up outside, chatting and waiting for their turn to loot. It was darkly funny: they almost looked like a normal line of people waiting at the checkout.

Suddenly one of them turned to me. "Why are you taking pictures? Did you ask my permission to take a photo of my premises? This is my shop and this is my street now, so fuck off." They became aggressive, and so I backed away with the other photographers.

Of course I wanted to stop them. This was somebody's shop, and what was really sad and silly was that these kids probably lived on this street. This was probably the newsagent where they bought their bread and milk. I wanted to shout, "Stop! How can you do this to your neighbours? Have you lost your minds?" But I didn't say anything. I just took photographs, and talked to the other photographers and onlookers. We were all saying, "Somebody should tell them to stop." But nobody did. We were all waiting for the police to come, and they didn't come for a very long time.

I feel bad about it. I was frightened, so I just stuck to my professional duty. But life as a photojournalist teaches you that during this kind of violence, getting involved won't end it; it will just lead to more people getting hurt. With the lootings, you're dealing with group psychology. A looter won't act like a person, they'll just go with the wave of action. You feel powerless, but the power you hold is in your job: to tell the story.

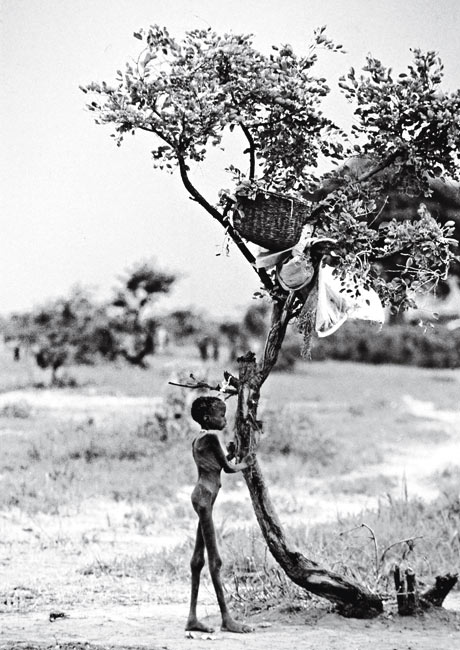

Famine, by Radhika Chalasani

'To this day, I think I didn't necessarily do the right thing'

Photograph: Radhika Chalasani

Photograph: Radhika ChalasaniSome photographers and journalists have a very absolute point of view that you never interfere, because your job is as an observer and you can do the most good by remaining one. I decided a long time ago that I had to do what I could live with in terms of my own conscience, so when it felt appropriate to try to do something, I would. There are certain situations you struggle with. We're interfering with a situation by our very presence, and that automatically changes the dynamic. At one point, I was photographing a woman carrying her son into a feeding centre. He was extremely malnourished, and I was photographing her as she walked along. All of a sudden, these Sudanese people started directing her for the photos. They had her sit down and were indicating how she should hold her child. I ran to get a translator, and said, "Tell her to take her child to the feeding centre. She should not be stopping because I'm taking a photograph."

Another time, there was a family sitting under a tree just outside the feeding centre, about 10 feet away. But they couldn't walk, they were so emaciated. And there was a group of photographers all around them. I took a few pictures, but then I walked into the feeding centre and asked a nurse, "Is there anything you can do for this family?"

I've been in situations where it's been a hard call, though. On one occasion, a group of photographers went into an abandoned refugee camp and found a massacre site. There were some children who had survived. There were two baby twins in a hut: I tried to get one child to take my hand and realised it had been chopped off. We didn't know how long they had been there. And it's in the middle of a civil war, so you're not sure how safe things are.

Myself and another photographer wanted to take the kids out of there in the car. Several of the other people didn't think it was safe, in case we got stopped at a checkpoint, and they wanted to get back for their deadlines. In the end, we didn't take the children. We found the Red Cross and reported the situation to them, but I found that another photographer went there the next day and found another child who was a survivor. To this day I think that I didn't necessarily do the right thing.

I do believe that our main contribution is trying to get the story understood. And sometimes, when you think you're helping, you're actually making a situation worse. But, for me, you try to do what you can live with.

0 comments:

Post a Comment